#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

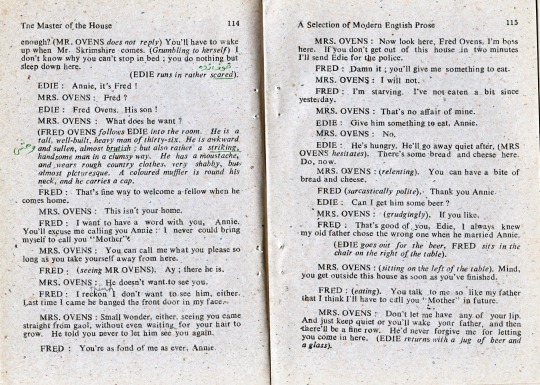

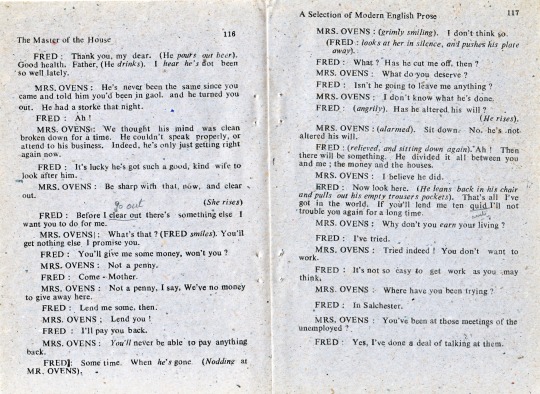

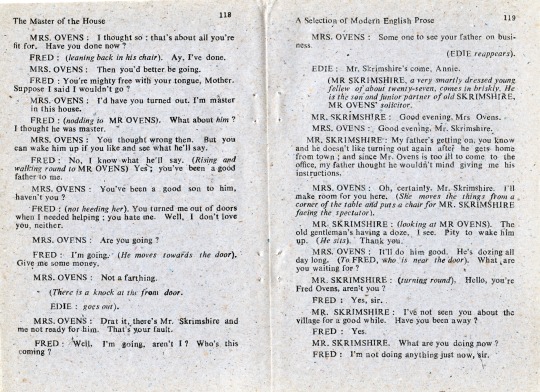

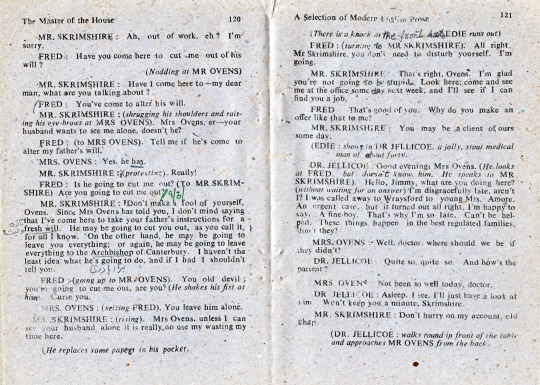

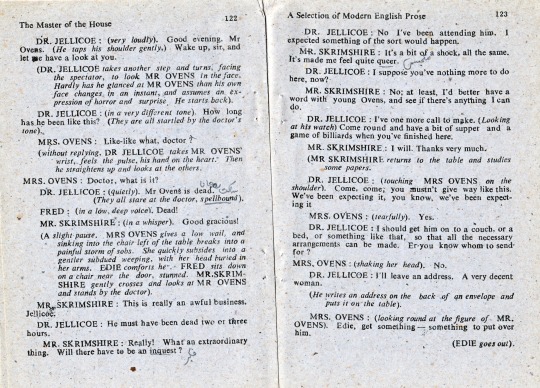

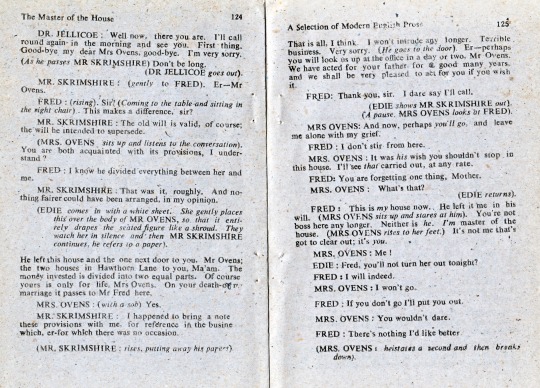

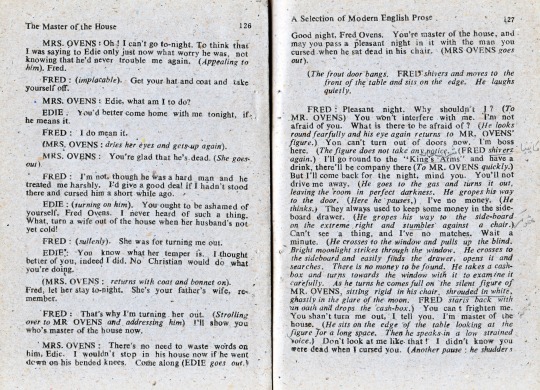

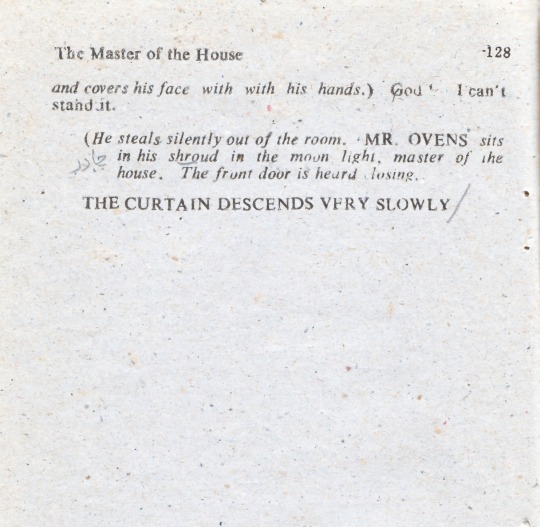

THE MASTER OF THE HOUSE

W.S. HOUGHTON

#THE MASTER OF THE HOUSE W.S. HOUGHTON#THE MASTER OF THE HOUSE#Stanley Houghton#William Stanley Houghton#play#stage drama#stage play#stage#drama#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Link

Sindh’s Covid restrictions to stay in place for two more weeks On the recommendations of the provincial task force on Covid-19, Sindh Chief Minister Syed Murad Ali Shah on Saturday announced that the coronavirus restrictions will stay in place for two more weeks due to the rise in the number of infection cases observed after Eidul Fitr. The provincial government has also decided to keep educational institutions closed until the Covid-19 situation improves, while beaches, amusement parks and other recreational places will also remain closed for another fortnight. The decision to maintain the pandemic-related restrictions was taken in the task force’s meeting, which was chaired by Shah and attended by provincial ministers and secretaries, health and infectious diseases experts, and representatives from WHO, the military and paramilitary forces. Keeping in view the rising trend of new cases and increasing death rate, it was decided to continue the ongoing restrictions for the next two weeks with strict standard operating procedures all over Sindh. The meeting was told that a record 24,299 tests were conducted on May 21, resulting in 2,136 positive cases, constituting 8.8 per cent detection rate, while 22 infected patients died the same day, which was termed a dangerous trend. It was disclosed that 17,197 travellers had landed at the Karachi airport between May 5 and 21, and their rapid antigen tests were conducted then and there, resulting in 38, or 0.22 per cent, of them turning out to be positive. Reviewing the post-Eid scenario, it was revealed that on Eid Day — May 13 — 1,232 positive cases were reported, and the number saw an abnormal increase to 2,136 on May 21. The meeting was told that during one week between May 15 to 21, the number of cases in Karachi’s District East had shown a 27 per cent detection rate, District South 15 per cent, District Central 13 per cent, and the Korangi, West and Malir districts 10 per cent, while Hyderabad and Dadu had shown an 11 per cent detection rate. The CM was told that during the past 30 days, 232 Covid patients had died, of them 164, or 71 per cent, in hospitals on ventilators and 42, or 18 per cent, off ventilators, while 26, or 11 per cent, died in their homes. The CM said Sindh had reported 154 deaths stemming from Covid-19 in April, but 232 deaths had already been reported in three weeks of the current month. “It means the situation is worsening.” Sharing the bed occupancy data, the health department said that out of the 664 ICU beds with ventilators, 68 are occupied, of them 64 in Karachi and two each in Hyderabad and Shaheed Benazirabad. Similarly, out of the 1,815 HDU beds, 558 are occupied, including 441 in Karachi, 45 in Hyderabad, 36 in Sukkur and 17 in Shaheed Benazirabad. The meeting was told that the government has so far received 1,007,000 doses of the Sinopharm vaccine, 47,000 of CanSino, 485,000 of Sinovac and 107,500 of AstraZeneca. So far 725,587 first doses have been administered and 255,132 second doses. Keeping in view the serious situation of the cases and the rising number of deaths, the CM decided to continue the ongoing restrictions for the next two weeks, announcing that the situation will be reviewed again on June 6 or 7. He also decided that all recreational places, including Sea View, Hawkesbay and amusement parks, will remain closed, but walking tracks in parks will remain open only for walking or jogging. It was decided that business hours will be from 6am to 6pm. All shops, including supermarkets, will have to close their business activities by 6pm sharp. “Educational institutions in the province will be opened when the Covid situation improves, otherwise they will remain closed,” said the CM, and directed the education minister to take the necessary measures to vaccinate teachers at all educational institutions. The meeting also decided that intercity transport will operate at 50 per cent of their seating capacity, warning that in case of any violation, transporters will be fined heavily. The meeting was also attended by ministers Dr Azra Pechuho and Saeed Ghani, CM’s adviser Murtaza Wahab, Chief Secretary Mumtaz Shah, Sindh police chief Mushtaq Mahar, CM’s Principal Secretary Sajid Abro, Karachi Commissioner Navid Shaikh, Karachi police chief Imran Minhas, Finance Secretary Hassan Naqvi, School Education Secretary Ahmed Narejo, Special Secretary Health Dr Abdul Bari, Dr Faisal Mehmood, Pakistan Medical Association General Secretary Dr Qaiser Sajjad, WHO’s Dr Sara Salman, Health Secretary Dr Kazim Jatoi, Dow University of Health Sciences Vice Chancellor Prof Dr Saeed Quraishy, and representatives of the V Corps and Rangers. https://timespakistan.com/sindhs-covid-restrictions-to-stay-in-place-for-two-more-weeks/19388/

0 notes

Photo

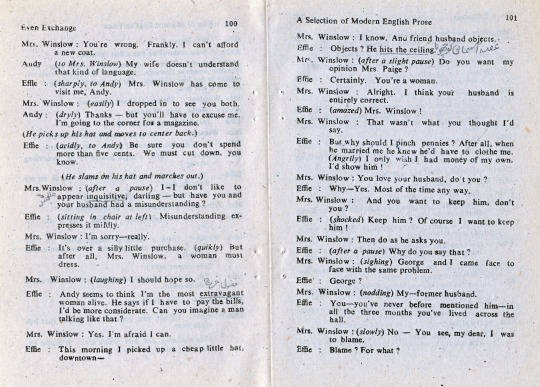

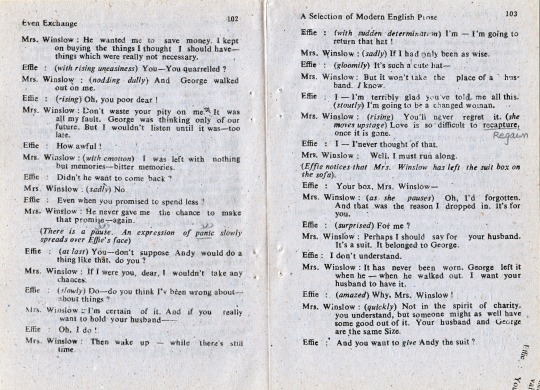

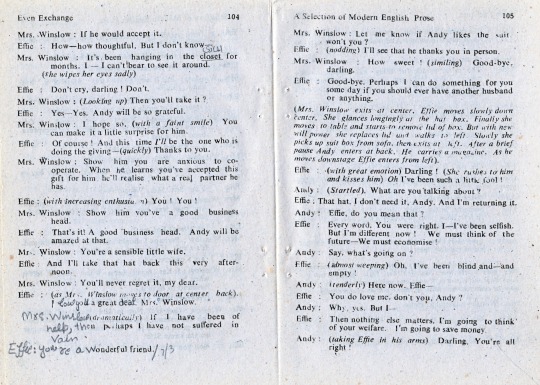

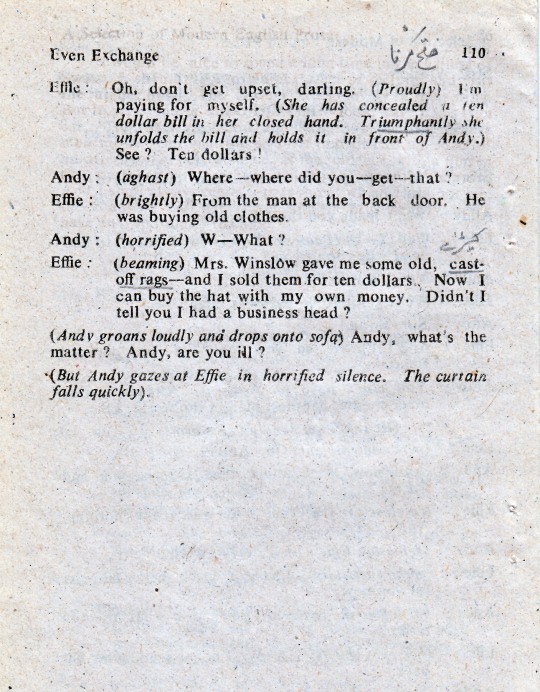

EVEN EXCHANGE

PAUL S. McCOY

#EVEN EXCHANGE PAUL S. McCOY#EVEN EXCHANGE by PAUL S. McCOY#EVEN EXCHANGE#DRAMA#STAGE DRAMA#STAGE#stage play#play#Satire#satirical#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Photo

GOODNIGHT, OLD DAISY

JOHN WAIN

#GOODNIGHT OLD DAISY JOHN WAIN#GOODNIGHT OLD DAISY by JOHN WAIN#John Wain#John Barrington Wain#John Barrington Wain CBE#GOODNIGHT OLD DAISY#play#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Photo

SPRING COMES TO THE FARM

BETTY F. MARTIN

#SPRING COMES TO THE FARM BETTY F. MARTIN#SPRING COMES TO THE FARM by BETTY F. MARTIN#SPRING COMES TO THE FARM#BETTY F. MARTIN#Betty Fible Martin#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Photo

ON BABIES

JEROME K. JEROME

#ON BABIES JEROME K. JEROME#ON BABIES by JEROME K. JEROME#ON BABIES#Jerome K. Jerome#Jerome Klapka Jerome#satire#humor#Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Photo

ONE VOTE FOR THIS AGE OF ANXIETY

MARGARET MEAD

#ONE VOTE FOR THIS AGE OF ANXIETY MARGARET MEAD#ONE VOTE FOR THIS AGE OF ANXIETY by MARGARET MEAD#ONE VOTE FOR THIS AGE OF ANXIETY#Margaret Mead#ANXIETY#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Photo

A VISIT TO THE SWAT VALLEY

H.P. STEWART

#A VISIT TO THE SWAT VALLEY H.P. STEWART#A VISIT TO THE SWAT VALLEY by H.P. STEWART#A VISIT TO THE SWAT VALLEY#SWAT VALLEY#H.P. STEWART#Hladia Porter Stewart#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Photo

SEEING LIFE

ARNOLD BENNETT

#SEEING LIFE ARNOLD BENNETT#SEEING LIFE by ARNOLD BENNETT#SEEING LIFE#Arnold Bennett#Enoch Arnold Bennett#A Selection of Modern English Prose#ENGLISH PROSE#Prose#Compiled and Edited by Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#Prof. SAJJAD SHAIKH#SAJJAD SHAIKH#for B.A. CLASSES#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS URDU BAZAR LAHORE#POLYMER PUBLICATIONS#URDU BAZAR LAHORE#URDU BAZAR#Lahore#Pakistan

0 notes

Link

On babies by Jerome K Jerome

#On babies by Jerome K Jerome#On babies#Jerome K Jerome#Jerome Klapka Jerome#A Selection of Modern English Prose#Prof. Sajjad Shaikh

0 notes

Text

One Vote for This Age of Anxiety by Margaret Mead

When critics wish to repudiate~ the world in which we live today, one of their familiar ways of doing it is to castigate modern man because anxiety is his chief problem. This, they say, in W.H. Auden's phrase, is the age of anxiety. This is what we have arrived at with all our vaunted~ progress, our great technological advances, our great wealth --everyone goes about with a burden of anxiety so enormous that, in the end, our stomachs and our arteries~ and our skins express the tension under which we live. Americans who have lived in Europe come back to comment on our favorite farewell which instead of the old goodbye (God be with you), is now "Take it easy," each American admonishing the 0ther not to break down from the tension and strain of modern life.

Whenever an age is characterized by a phrase, it is presumably in contrast to other ages. If we are the age of anxiety, what were other ages? And here the critics do a very amusing thing. First, they give us lists of the opposites of anxiety: security, trust, self-confidence, self-direction. Then, without much further discussion, they let us assume that other ages, other periods of history, were somehow the ages of trust or confident direction.

The savage who, on his South Sea island, simply sat and let bread fruit fall into his lap, the simple peasant, at one with the fields he ploughed and the beasts he tended, the craftsman busy with his tools and lost in the fulfillment of the instinct of workmanship --these are the counter-images conjured up by descriptions of the strain under which men live today. But no one who lived in those days has returned to testify how paradisiacal they really were.

Certainly if we observe and question the savages or simple peasants in the world today, we find something quite different. The untouched savage in the middle of New Guinea isn't anxious; he is seriously and continually frightened --of black magic~, of enemies with spears who may kill him or his wives and children at any moment, while they stoop to drink from a spring, or climb a palm tree for a coconut. He goes warily, day and night, taut and fearful.

As for the peasant populations of a great part of the world, they aren't so much anxious as hungry. They aren't anxious about whether they will get a salary raise, or which of the three colleges of their choice they will be admitted to, or whether to buy a Ford or Cadillac, or whether the kind of TV set they want is too expensive. They are hungry, cold and, in many parts of the world, they dread that local warfare, bandits, political coups may endanger their homes, their meager livelihoods, and their lives. But surely they are not anxious.

For anxiety, as we have come to use it to describe our characteristic state of mind, can be contrasted with the active fear of hunger, loss, violence, and death. Anxiety is the appropriate emotion when the immediate personal terror --of a volcano, an arrow, the sorcerer's~ spell, a stab in the back and other calamities, all directed against one's self--disappears.

This is not to say that there isn't plenty to worry about in our world of today. The explosion of a bomb in the streets of a city whose name no one had ever heard before may set in motion forces which end up by ruining one's carefully planned education in law school, half a world away. But there is still not the personal, immediate, active sense of impending~ disaster that the savage knows. There is rather the vague anxiety, the sense that the future is unmanageable.

The kind of world that produces anxiety is actually a world of relative safety, a world in which no one feels that he himself is facing sudden death. Possibly sudden death may strike a certain number of unidentified other people -- but not him. The anxiety exists as an uneasy state of mind, in which one has a feeling that something unspecified and undeterminable may go wrong. If the world seems to be going well, this produces anxiety -- for good times may end. If the world is going badly -- it may get worse. Anxiety tends to be without focus; the anxious person doesn't know whether to blame himself or other people. He isn't sure whether it is 1956 or the Administration or a change in climate or the atom bomb that is to blame for this undefined sense of unease.

It is clear that we have developed a society which depends on having th eright amount of anxiety to make it work. Psychiatrists have been heard to say, "He didn't have enough anxiety to get well," indicating that, while we agree that too much anxiety is inimical to mental health, we have come to rely on anxiety to push and prod us into seeing a doctor about a symptom which may indicate cancer, into checking up on that old life-insurance policy which may have out-of-date clauses in it, into having a conference with Billy's teacher even though his report card looks all right.

People who are anxious enough keel their car insurance up. have the brakes checked I don't take a second drink when they have to drive, are careful where they go and with whom they drive on holidays. People who are too anxious either refuse to go into cars at all -- and so complicate the ordinary course of life -- or drive so tensely and overcautiously that they help cause accidents. People who aren't anxious enough take chance after chance, which increases the terrible death toll of the roads.

On balance, our age of anxiety represents a large advance over savage and peasant cultures. Out of a productive system of technology drawing upon enormous resources, we have created a nation in which anxiety has replaced terror and despair, for all except the severely disturbed. The specter of hunger means something only to those Americans who can identify themselves with the millions of hungry people on other continents. The specter of terror may still be roused in some by a knock at the door in a few parts of the South. or in those who have just escaped from a totalitarian regime or who have kin still behind the Curtains.

But in this twilight~ world which is neither at peace nor at war, and where there is insurance against certain immediate, downright, personal disasters, for most Americans there remains only anxiety over what may happen, might happen. could happen.

This is the world out of which grows the hope, for the first time in his story, of a society where there will be freedom from want and freedom from fear. Our very anxiety is born of our knowledge of what is now possible for each and for all. The number of people who consult psychiatrists today is not. as is sometimes felt, a symptom of increasing mental iii health, but rather the precut sot of a world in which the hope of genuine mental health will be open to everyone, a world in which no individual feels that be need be hopelessly broken hearted, a failure, a menace to others or a traitor to himself.

But if, then, our anxieties are actually signs of hope, why is there such a voice of discontent abroad in the land? I think this comes perhaps because our anxiety exists without an accompanying recognition Of the tragedy which will always be inherent in human life. however well we build our world. We may banish hunger, and fear of sorcery, violence, or secret police; we may bring up children who have learned to trust life and who have the spontaneity and curiosity necessary to devise ways of making trips to the moon; we cannot as we have tried to do -- banish death itself.

Americans who stem from generations which left their old people behind and never closed their parents' eyelids in death, and who have experienced the additional distance from death provided by two world wars fought far from our shores are today pushing away from them both a recognition of death and are cognition of the tremendous significance -- for the future -- of the way we live our lives. Acceptance of the inevitability of death, which, when faced, can give dignity to life. and acceptance of our inescapable role in the modern world, might transmute~ our anxiety about making the right choices, taking the right precautions, and the right risks into the sterner stuff of responsibility, which ennobles the whole face rather than furrowing~ the forehead With the little anxious wrinkles of worry.

Worry in an empty context means that men die daily little deaths. But good anxiety -- not about the things that were left undone long ago, but which return to haunt and hardy men's minds, but active, vivid anxiety about what must be done and that quickly binds men to life with an intense concern.

This is still a world in which too many of the wrong things happen somewhere. But this is a world in which we now have the means to make a great many more of the right things happen everywhere. For Americans, the generalization which a Swedish social scientist made about our attitudes on race relations is true in many other fields: anticipated change which we feel is right and necessary but difficult makes us unduly anxious and apprehensive, but such change, once consummated, brings a glow of relief. We are still a people who -- in the literal sense -- believe in making good.

#One Vote for This Age of Anxiety by Margaret Mead#One Vote for This Age of Anxiety#Margaret Mead#Age of Anxiety#Anxiety#A Selection of Modern English Prose#Prof. Sajjad Shaikh

0 notes

Text

SEEING LIFE by ARNOLD BENNETT

A young dog, inexperienced, sadly lacking in even primary education, ambles and frisks along the footpath of Fulham Road, near the mysterious gates of a Marist convent. He is a large puppy, on the way to be a dog of much dignity, but at present he has little to recommend him but that gawky elegance, and that bounding gratitude for the gift of life, which distinguish the normal puppy. He is an ignorant fool. He might have entered the convent of nuns and had a fine time, but instead he steps off the pavement into the road, the road being a vast and interesting continent imperfectly explored. His confidence in his nose, in his agility, and in the goodness of God is touching, absolutely painful to witness. He glances casually at a huge, towering vermilion construction that is whizzing towards him on four wheels, preceded by a glint of brass and a wisp of steam; and then with disdain he ignores it as less important than a mere speck of odorous matter in the mud. The next instant he is lying inert in the mud. His confidence in the goodness of God had been misplaced. Since the beginning of time God had ordained him a victim.

An impressive thing happens. The motor-bus reluctantly slackens and stops. Not the differential brake, nor the foot-brake, has arrested the motor-bus, but the invisible brake of public opinion, acting by administrative transmission. There is not a policeman in sight. Theoretically, the motor-'bus is free to whiz onward in its flight to the paradise of Shoreditch, but in practice it is paralysed by dread. A man in brass buttons and a stylish cap leaps down from it, and the blackened demon who sits on its neck also leaps down from it, and they move gingerly towards the puppy. A little while ago the motor-bus might have overturned a human cyclist or so, and proceeded nonchalant on its way. But now even a puppy requires a post-mortem: such is the force of public opinion aroused. Two policemen appear in the distance.

"A street accident" is now in being, and a crowd gathers with calm joy and stares, passive and determined. The puppy offers no sign whatever; just lies in the road. Then a boy, destined probably to a great future by reason of his singular faculty of initiative, goes to the puppy and carries him by the scruff of the neck, to the shelter of the gutter. Relinquished by the boy, the lithe puppy falls into an easy horizontal attitude, and seems bent upon repose. The boy lifts the puppy's head to examine it, and the head drops back wearily. The puppy is dead. No cry, no blood, no disfigurement! Even no perceptible jolt of the wheel as it climbed over the obstacle of the puppy's body! A wonderfully clean and perfect accident!

The increasing crowd stares with beatific placidity. People emerge impatiently from the bowels of the throbbing motor-bus and slip down from its back, and either join the crowd or vanish. The two policemen and the crew of the motor-bus have now met in parley. The conductor and the driver have an air at once nervous and resigned; their gestures are quick and vivacious. The policemen, on the other hand, indicate by their slow and huge movements that eternity is theirs. And they could not be more sure of the conductor and the driver if they had them manacled and leashed. The conductor and the driver admit the absolute dominion of the elephantine policemen; they admit that before the simple will of the policemen inconvenience, lost minutes, shortened leisure, docked wages, count as less than naught. And the policemen are carelessly sublime, well knowing that magistrates, jails, and the very Home Secretary on his throne—yes, and a whole system of conspiracy and perjury and brutality—are at their beck in case of need. And yet occasionally in the demeanour of the policemen towards the conductor and the driver there is a silent message that says: "After all, we, too, are working men like you, over-worked and under-paid and bursting with grievances in the service of the pitiless and dishonest public. We, too, have wives and children and privations and frightful apprehensions. We, too, have to struggle desperately. Only the awful magic of these garments and of the garter which we wear on our wrists sets an abyss between us and you." And the conductor writes and one of the policemen writes, and they keep on writing, while the traffic makes beautiful curves to avoid them.

The still increasing crowd continues to stare in the pure blankness of pleasure. A close-shaved, well-dressed, middle-aged man, with a copy of The Sportsman in his podgy hand, who has descended from the motor-bus, starts stamping his feet. "I was knocked down by a taxi last year," he says fiercely. "But nobody took no notice of that ! Are they going to stop here all the blank morning for a blank tyke?" And for all his respectable appearance, his features become debased, and he emits a jet of disgusting profanity and brings most of the Trinity into the thunderous assertion that he has paid his fare. Then a man passes wheeling a muck-cart. And he stops and talks a long time with the other uniforms, because he, too, wears vestiges of a uniform. And the crowd never moves nor ceases to stare. Then the new arrival stoops and picks up the unclaimed, masterless puppy, and flings it, all soft and yielding, into the horrid mess of the cart, and passes on. And only that which is immortal and divine of the puppy remains behind, floating perhaps like an invisible vapour over the scene of the tragedy.

The crowd is tireless, all eyes. The four principals still converse and write. Nobody in the crowd comprehends what they are about. At length the driver separates himself, but is drawn back, and a new parley is commenced. But everything ends. The policemen turn on their immense heels. The driver and conductor race towards the motor-bus. The bell rings, the motor-bus, quite empty, disappears snorting round the corner into Walham Green. The crowd is now lessening. But it separates with reluctance, many of its members continuing to stare with intense absorption at the place where the puppy lay or the place where the policemen stood. An appreciable interval elapses before the "street accident" has entirely ceased to exist as a phenomenon.

The members of the crowd follow their noses, and during the course of the day remark to acquaintances:

"Saw a dog run over by a motor-bus in the Fulham Road this morning! Killed dead!"

And that is all they do remark. That is all they have witnessed. They will not, and could not, give intelligible and in teresting particulars of the affair (unless it were as to the breed of the dog or the number of the bus-service). They have watched a dog run over. They analyse neither their sensations nor the phenomenon. They have witnessed it whole, as a bad writer uses a cliché . They have observed—that is to say, they have really seen—nothing.

#SEEING LIFE by ARNOLD BENNETT#SEEING LIFE#Arnold Bennett#Enoch Arnold Bennett#A Selection of Modern English Prose#Prof. Sajjad Shaikh

0 notes